'A Liar and....Perverting Rascal"

How the Debate to Treat Yellow Fever in 18th Century Philadelphia Turned Political and Violent

In the summer of 1797 the City of Philadelphia was in the grip of another yellow fever epidemic. More a than a thousand people would be killed by the time of the first frost.

Prominent Philadelphia physician Dr. Benjamin Rush – a member of the Continental Congress and signer of the Declaration of Independence – believed he had a treatment.

Rush’s purging powder (used to make patients vomit and “evacuate” their bowels) - coupled with the bleeding of patients - was part of Rush’s treatment regimen.

Not everyone in Philadelphia however agreed with the doctor’s method of treatment.

Among Rush’s critics were Dr. Edward Stevens and German-American Doctor Adam Kuhn - who had argued in favor of a less severe series of remedies common in the West Indies where yellow fever was more prevalent.

Their treatment - that included bed rest and cold baths - did not weaken patients and had gained the support of one of the nation’s leading figures Alexander Hamilton (who had been adopted by Stevens’ father while still a child in the West Indies).

Like coronavirus centuries later disagreements over how to treat yellow fever quickly turned political and even violent. On one side of the debate were Hamilton and the Federalists. On the other were Rush (who had supported Thomas Jefferson’s election the year earlier) and the Democratic-Republicans (the party of Jefferson and his supporters).

One particular letter criticizing Rush’s bleeding treatments - that appeared in the Gazette of the United States - particularly angered the doctor’s son John.

Rush erroneously believed the letter had been written by an aging Scottish physician, then practicing in Philadelphia, named Dr. Andrew Ross.

Bad feelings soon simmered over into violence.

“However disposed my father may have been to treat the numerous calumnies published against him with silence and to await the decision of a jury of his fellow citizens upon them, I have not been able to reduce my feelings to the same degree of composure,” John later wrote in the Gazette.

Brandishing a cane and his own fists John set out to set things right.

The roots of this soon to be violent encounter began much earlier during the fever outbreak of 1793.

In late August of that year Dr. Rush began to experiment with different treatments – inducing vomiting, blistering, wrapping his patients in vinegar soaked blankets and rubbing the sick with mercurial lotions. All failed.

“Perplexed and distressed by a want of success in the treatment of this fever I waited upon Dr. Stevens, an eminent and respectable physician from St. Croix who then happened to be in our city and asked for such advice and information upon the subject of the disease,” Rush later explained.

Stevens suggested bark, wine and cold baths. Rush tried each – even throwing buckets of cold water on his sick patients. Three out of four patients died.

Frustrated Rush looked elsewhere for a treatment.

“I ransacked my library and poured over every book” regarding the fever,” he later recalled.

Then Rush remembered a dusty, old manuscript – given to him by the late Benjamin Franklin shortly before his death – regarding an outbreak of yellow fever in Virginia in 1741. Rush read over the book a second time coming to a section regarding the success of “evacuations” (presumably vomiting, bleeding and of the bowels) during that epidemic.

“Here I paused. A new train of ideas suddenly broke in upon my mind,” Rush later recalled.

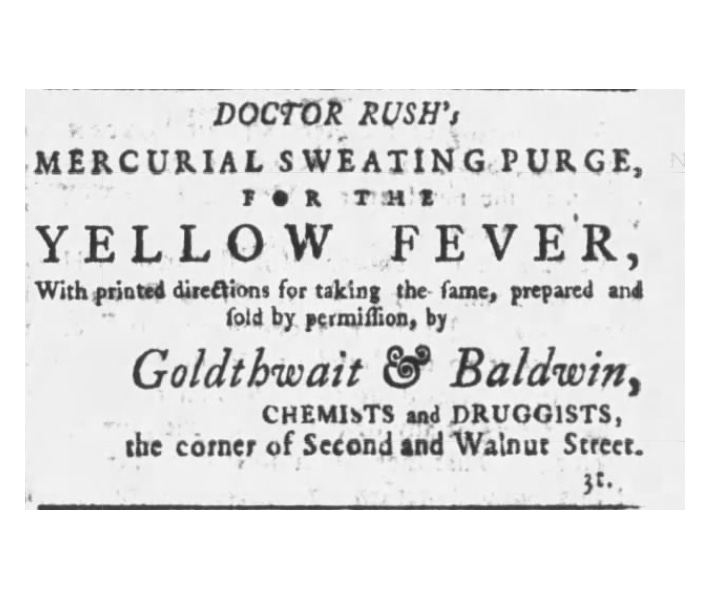

By early September Rush was using these new treatments that included purges, bleeding, cool air, cold drinks and the application of cold water to the body. Soon he was swamped with requests for his purging powders that were advertised in the local papers.

Dr. Adam Kuhn – a German-American physician with a successful practice in Philadelphia - subsequently wrote a letter which appeared in the General Advertiser arguing against bleeding and purges and in favor of less severe treatments used in the West Indies.

These treatments included wine infused with mint and spices, a diet of ripe fruits, washing the body with vinegar, clean bed sheets and the application of cold water twice a day to patients in a tub.

Rush disagreed with this brand of treatment – erroneously arguing that the yellow fever in Philadelphia wasn’t the same as the fever in the West Indies.

“I am satisfied that the mode of treating it which I have adopted and recommended would soon reduce it in point of danger and mortality to a level with a common cold,” Rush boasted in the papers. Some patients Rush would bleed as much as four times.

In reality Rush’s bleeding treatments only weakened his patients and made it more likely they would die from the fever.

The ongoing debate - over how to best treat the ailment - for Rush became, not an honest disagreement between he and his fellow doctors, but rather a personal attack on himself. According to Rush the doctors who now attacked him were jealous of his innovative treatments introduced prior to the Revolution and of his politics.

“That part I took in favor of my country in the American Revolution had left prejudices in the minds of the most wealthy citizens of Philadelphia against me, for a great majority of them had been Loyalists in principle and conduct,” he later would argue.

Rush came to view his treatment in messianic terms - seeing himself as no less than an “instrument” of God. The success of his treatments Rush argued “produced a sudden combination of all who had been either publicly or privately my enemies and the most violent and undisguised exertions to oppose and discredit those remedies…”

When the fever returned to Philadelphia in 1797 the debate over treatment became even more bitter and divisive. Rush became a target of the Federalist newspapers and one publisher in particular – William Cobbett.

The son of an English day laborer – who had supported the American Revolution – Cobbett initially was an admirer of the American pamphleteer Thomas Paine. News of the French king’s beheading however – while Cobbett was in Paris (after leaving the British Army) – turned him away from republicanism.

Cobbett left France and traveled to Philadelphia where he taught French refugees English for $6 a month. There he became a vocal opponent of the French Revolution and a Federalist in his politics - referring to the author of Common Sense, in one of his pamphlets, as “Patriot Paine the heathen philosopher.” He also wrote in favor of the Jay Treaty and good relations between Britain and America.

In July of 1796 Cobbett opened a bookshop. In an effort to antagonize the Democratic-Republicans and Jefferson supporters he so despised Cobbett put together a “grand exhibition of the portraits of kings, queens, princes, nobles and bishops….in short….every portrait, picture or book that I could obtain and that I thought likely to excite rage in the inveterate enemies of Great Britain,” Cobbett later recalled. He even hung a picture of King George III in his shop window.

Threatened with tar and feathering and the destruction of his home on Second Street, “Peter Porcupine” - as he signed his pamphlets and letters - lambasted the Jeffersonians, making numerous enemies even among some Federalists.

When it became known among the wider public that Cobbett was Porcupine the prickly pamphleteer embraced his former pen name and used it for the name of a new newspaper – Porcupine’s Gazette and Daily Advertiser - that he first published in early March of 1797.

One of Cobbett’s favorite targets became Dr. Rush. Cobbett accused the doctor’s mother – who had run a grocery store and provision shop on Market Street following her husband’s death (when Rush was still a young child) – as keeping a “huckster’s shop. He also accused Rush of being a vain boaster, a quack, a sangrado responsible for the death of his patients. Rush’s treatments had killed more people than Samson did the Philistines claimed Cobbett.

When the letter appeared in the Gazette of the United States attacking his father’s treatments, Rush’s son John had enough. He decided to confront Ross whom he falsely believed had penned the letter.

“I called at his house to ask him whether or not he was the author of that performance: not finding him at home I sent him the next day the following note: ‘…I take this method of demanding whether you are or are not the author of the said publication. Your silence on the matter, shall be considered as an acknowledgement of your guilt,” John Rush later recounted.

When Ross sent back a reply claiming not to know either Benjamin or John, the latter sent another note to Ross.

Upon receiving Rush’s latest missive Ross was overheard by Rush’s messenger referring to the young upstart as a “impertinent puppy.”

“‘I don’t understand why you take the liberty to call on me for any newspaper abuse you or your father complain of – I surely never did nor never intend to write any observations on any physicians’ conduct or practice and sincerely regret the unworthy conduct of both printers,’” Ross wrote Rush.

“This would have satisfied me had it not been accompanied with the epithet he applied to me,” John later explained.

The young hot head wrote Ross another note. “The unpolite manner in which you treated my note of this morning and the epithet…which you have applied to me, demand satisfaction. If you refuse to give it to me I shall consider you a scoundrel and treat you accordingly,” John Rush wrote back.

Rush then confronted Ross with his note which was read to the aging doctor in Rush’s presence.

“I asked him whether or not he called me an ‘impertinent puppy.’ This question he hesitated in answering but upon Mr. Bullus declaring he had used those expressions…” Ross then acknowledged he had according to Rush.

“Upon this I struck him first with my fist and then with [my] cane. He retired; I waited to hear from him during the remaining part of the day. In the evening I was surprised to find he sent the following note to my father,” Rush recalled.

The note requested Dr. Rush meet Ross in New Jersey with a friend for what – while not expressly stated – would have commonly been understood to be a duel.

“The sole purpose of the meeting is to have personal satisfaction of Dr. Rush for the ruffian assault of his son this morning of which he considers the Dr. as the sole instigator,” read the note.

The elder Rush penned a quick reply. “I do not fear death but I dare not offend God by exposing myself or a fellow creature to the chance of committing murder,” he wrote.

Dr. Rush forgave Ross of injury and denied instigating his son to attack the doctor. Rush also asked for Ross to be arrested for challenging him to a duel.

When Cobbett found out about the incident he was blistering in his attack. “What shall be said of the base wretch who sets his son and domestic, armed with bludgeons to waylay a gentleman and to beat him and who when called on himself to answer for that offense flies to a justice of the peace and binds over the injured challenger. Oh the exalted mind – Oh the fiend to humanity! Many a man is brave with a lancet who dares not look at a sword,” wrote Cobbett.

John Rush was quick to shoot back at Cobbett. “I must stigmatize you a liar and a perverting rascal. You call yourself an Englishman. Englishmen are brave but you are a coward. Some men are brave with a pen who dare not handle a pistol,” wrote Rush.

Rush’s challenge was hardly vain boasting. Years later he would be involved in a deadly duel that took the life of a dear friend.

In 1807 – while a sailing master in the U.S. Navy, in command of a gunboat at New Orleans – Rush shot and killed one of his good friends following an argument over - of all things - Shakespeare.

“A number of officers were amusing themselves in their quarters last evening with cards. Then R. [Rush] came in [and] was asked to play,” a serviceman later recalled in the newspapers.

Rush declined the invitation quoting Shakespeare. This led to an argument between he and his friend. Bad language was passed. Rush’s friend sent a challenge. They met at night outside the city. Two volleys were shot. During the second Rush’s friend and fellow officer was struck by a bullet that entered his sleeve and struck his body. Rush’s friend struggled for a few steps before declaring “I am dead,” and falling over into the arms of his companions. He then died.

“R. was much affected and embraced him in the agonies of death, exclaiming in a frantic manner ‘my dear friend! Why would you force me to this? Let me declare in your dying ear that I had no enmity to you – that I did not wish to meet you – and that I shall mourn your death as that of a brother,” the serviceman later recalled in the papers.

Rush never recovered from the incident. The killing of his friend drove him to madness. He would spend 37 years in a Philadelphia hospital where he would die unmarried.

In Philadelphia however cooler heads prevailed and Rush and Cobbett never met on the dueling grounds of New Jersey or elsewhere. Instead the elder Rush went to court - suing Cobbett for libel two years later.

From the onset the trial seemed stacked in Rush’s favor. According to one account, of the 48 potential jurors for the trial, Cobbett could only find seven he believed would be fair to him. All of those seven were said to have been struck by Rush from serving on the jury.

The jurors deliberated for just two hours and returned a verdict in Rush’s favor for $5,000 in damages.

Cobbett was financially ruined. His property in Philadelphia was auctioned off and he was forced to suspend the publication of his newspaper. He left Philadelphia for New York and soon announced he would publish a new newspaper.

Having not lost his sense of humor or willingness to antagonize his opponents Cobbett called the new publication the Rushlight.

Only three editions however were printed of the new paper. In June of 1800 Cobbett sailed for England where he would later serve in Parliament.

Eventually bleeding would be discredited as a form of treatment for yellow fever and other ailments yet not before Cobbett’s libel trial.

The second day of Cobbett’s trial, unbeknownst to those in the court room, President George Washington lay dying on his bed at Mount Vernon. He had been bled four times.

SOURCES

Account of Bilious Remitting Yellow Fever Benjamin Rush 1796 pg. 40-55, 153-157

Colonial Families of Philadelphia John W. Jordan Editor Vol. I, The Lewis Publishing Company NY 1911 pg. 529

Smith College Studies in History, John Spencer Bassett and Sidney Bradshaw editors. Vol. V

1919-1920 History Dept. Smith College MA pg. 16-17

The History of Medicine in the United States by Francis Randolph Packard, J.B. Lippincott Co. 1901 Phild. Pg. 140-142

American Bar Association Journal Vol. 46 No. 2 February 1960 Chicago “Books For Lawyers American Bar Association Journal Feb. 1960 vol. 46 “Verdict for the Doctor, the Case of Benjamin Rush By Winthrop and Francis Neilson” a review of the book by Raymond Coward pg. 191-192

Biographies of John Wilkes and William Cobett Rev. John Shelby Watson, William Blackwood and Sons, London 1870 pg. 199-209

William Cobett: A Study of His Life As Shown in His Writings E. I. Carlyle, Archibald Constable and Company 1904 pgs. 1-74

William Cobett: A Study of His Life As Shown in His Writings E. I. Carlyle, Archibald Constable and Company 1904 pgs. 1-74

The Philadelphia Inquirer October 19, 1797

United States Naval Institute Proceedings Vol. 35, 1909 Anapolis, Published by U.S. Naval Institute pg. 1166

Index to the Executive Documents of the 31st Congress Second Session U.S. Govt. Printing Office “Claim of the Administrator of John Rush for Arreage Pay” Feb. 1851” pg. 2128 and 2129

The Gleaner November 27, 1807